|

My wife is from Seattle, and we were planning a family visit in October of this year anyway. So, I researched to see if there were any Shinto services to attend, first. I was lucky that we could shift our travel plans to include the Great Fall Purification ritual (Shyu-ki Taisai) took place at Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America (http://www.tsubakishrine.org/) on Sunday October 15, 2017.

There were 14 rows of 10 chairs each, but there were also people sitting on the floor on the left side of the seating area, beyond the chairs. Perhaps 160 people were observing the ritual, not counting volunteers, ushers, and the head priest. The mix was approximately 60 percent people of Asian descent and 40 percent Anglos. The men and women were intermixed throughout the crowd, and there were a few children present. Most of the children were babes in

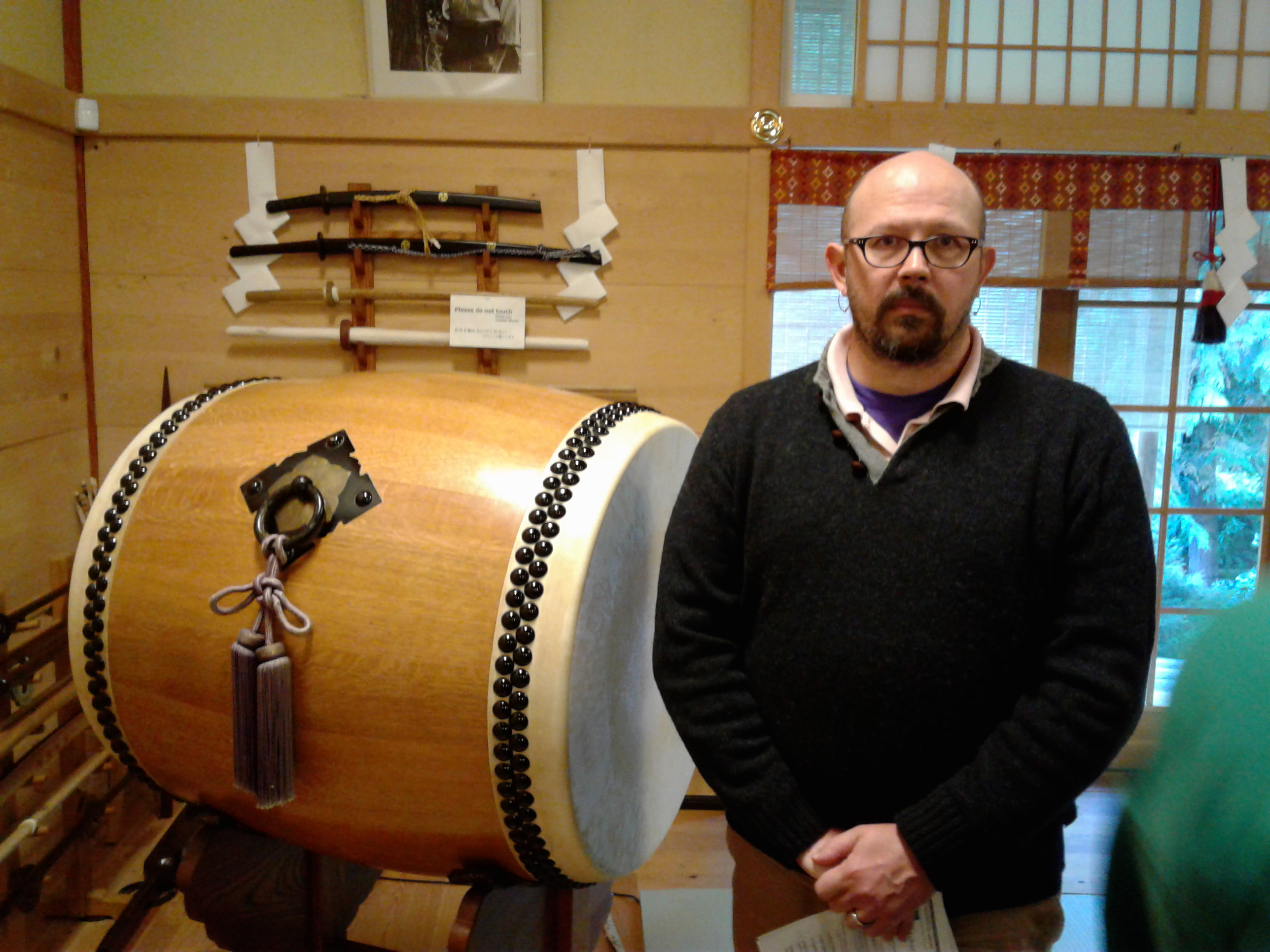

As the ceremony started, the priest struck a large drum in the back left of the space, over 25 times, but with varying timing and rhythms. Then he walked across the back of the hall and up the right side to the front. Once he reached the front and settled into the down front, stage left corner, he began to chant a prayer in Japanese. At that moment I felt a surge of power as the kami entered the room. The rest of the ceremony was a mix of silent sitting, standing, and bowing, with occasional hand clapping, at the instruction of the head priest. I nodded out a little during the middle of the ceremony, because of the warmth of my sweater and the droning sounds of the background flute

I interacted with no one beside the onsite staff on location, before or after the ritual, as the head priest previously requested I not disturb people. I did, however, manage electronic correspondence with 3 adherents: Rev. Richard Boeke (a retired Unitarian Universalist minister who now practices Shinto) via email, Megan Manson (a neopagan who incorporates Shinto practices into her life and worship) via the Shinto Facebook group, and Jerry Jorgenson (a Shinto adherent) via Facebook messenger. Jerry likes the simplicity, harmony, and equality of all things (kami, people, animals, plants, etc.) in Shintoism. He practices Shinto because it is a lifestyle, not a fear reaction to a specific deity or an attempt to "impress the neighbors." Megan directed me to her blog post on the subject, which states that Shintoism allowed her to reconcile her need for science and her need for a spiritual path. She practices both Shintoism and Wicca together, because they both "focus on ritual, nature worship and sense of duty to the ancestors." Rev. Boeke loves the closeness to nature, the wonder of the universe, and the affirmation of both life and science. Shintoism is, apparently, very similar to my own Wicca practice. There is a choice of which kami to venerate, and Shinto practitioners work with the kami to whom they are most drawn. I, similarly, choose my own pantheon by which gods/goddesses are easiest to work with or that I feel drawn toward. Both traditions celebrate the cycle of the seasons and view the world as something to be stewarded, not dominated nor lorded over. Both traditions stay in contact with our ancestors. It seems that both seek peace and harmony within nature. Both do ritual cleansing. Both also seem to make loud noises to attract our gods. Both make ritual offerings. Also, both can coexist with science. I discovered that this religion grew out of people who work fields to live. That explains that the individual shrines at home, much like Wicca. Similarly, we both celebrate the solar holidays in community. Although, I do not know if Shinto also celebrates the lunar cycle. Looking back, the visit was a very pleasant one. I felt very safe during the visit (the dojo aspects really helped me feel more familiar), despite my apprehension at not doing it right as a newcomer. The ritual purification was not as complicated as I feared from reading about it on the website FAQ. I saw how the other people performed their tasks, and I easily followed their lead in bowing appropriately. There were also some signs in English on the outside with instructions to ease my fear that I would forget something or mismanage the water and bell pull. To make this a more productive experience in the future, I would try to visit the grounds ahead of time. I would also show up even earlier than the 30 minutes that I did, to get a seat closer to the front. Further, I would read up more on the particular kami enshrined at the location to see if wearing specific colors would be more appropriate or not. I discovered that this is a very quiet, reflective, and personalized religion. Venerating ancestors is very personal. Managing a relationship with the kami is very personal. I discovered that the religion has evolved over the years, from kami living on top of mountains, to kami being enshrined. I am not sure whether this is good or bad. Having a shrine with a roof certainly makes it more comfortable to worship in foul weather, though. This encounter showed me that, if I could not find a coven in Japan, I could easily find peace at Shinto shrines. In fact, I already have a link to something Shinto, in that I have kitsune as spirit guides. I assumed that I would be sitting on the floor in lotus or seiza positions for the ritual, and I was very pleased to find that chairs were employed. I was glad that the offerings were already harvested, unlike Santeria's live animals, and I was grateful that no one required me to partake of the purified sake, unlike Catholicism's Communion wine, Asatru's toasting with mead, or Druidism's ritual consumption of whiskey. I am curious, still, about the various levels of purification, both personally and of the grounds and areas of the building, and about the stages of life rituals. More reading of the textbook would be a good start for this, but I also have that Shinto Facebook group available to query. Some scenes from the grounds:

|

| Created by Laura Ellen Shulman |

Last updated: December 27, 2017

|

A wide gravel path led from the road, through a large gate (torii), and wended downhill, through old-growth woods, to a stream-side area, with just enough room cleared out for the building and a few displays of sculpture. The parking area was across the street from the shrine grounds. The pathways were all gravel, well-kept and free of grass or weeds growing through the stones. The building, itself, did not look large from the outside, but it blended harmoniously in with the forest, too. From the outside, the building appeared to be somewhat contemporary, until I turned the corner of the path to the entrance of the building. That is when I saw the gates, purification station, and the bell pull station. They were clearly ancient Asian architecture. The building was not aligned to any cardinal direction, although some others are apparently opened to the east or south. It appeared to have traditional Japanese architecture and decoration inside. In fact, it appeared to double as an Aikido dojo when not in use for ceremonies. There was an entryway just after the purification station and the bells that were to be rung to announce your presence. In the entryway, people took off their shoes, placed the shoes on shelves built for the purpose, and proceeded, sock-footed, up some stairs into the main area. There was a set of bathrooms off to the right, and a dressing room for the officiants, in the short hallway between the entryway and the stairs. An additional set of stairs continued up to a second level, where people registered and paid their entrance fees. The main area was two stories high. The floors were wooden around the edges, but soft mats covered most of the center of the floor. Wooden chairs were brought out of storage, expressly for seating people

A wide gravel path led from the road, through a large gate (torii), and wended downhill, through old-growth woods, to a stream-side area, with just enough room cleared out for the building and a few displays of sculpture. The parking area was across the street from the shrine grounds. The pathways were all gravel, well-kept and free of grass or weeds growing through the stones. The building, itself, did not look large from the outside, but it blended harmoniously in with the forest, too. From the outside, the building appeared to be somewhat contemporary, until I turned the corner of the path to the entrance of the building. That is when I saw the gates, purification station, and the bell pull station. They were clearly ancient Asian architecture. The building was not aligned to any cardinal direction, although some others are apparently opened to the east or south. It appeared to have traditional Japanese architecture and decoration inside. In fact, it appeared to double as an Aikido dojo when not in use for ceremonies. There was an entryway just after the purification station and the bells that were to be rung to announce your presence. In the entryway, people took off their shoes, placed the shoes on shelves built for the purpose, and proceeded, sock-footed, up some stairs into the main area. There was a set of bathrooms off to the right, and a dressing room for the officiants, in the short hallway between the entryway and the stairs. An additional set of stairs continued up to a second level, where people registered and paid their entrance fees. The main area was two stories high. The floors were wooden around the edges, but soft mats covered most of the center of the floor. Wooden chairs were brought out of storage, expressly for seating people

for the ceremony. The worship room was approximately 60 feet wide, 80-100 feet long, and more than a story high. There were windows on both the left and right sides of the space and skylights. The

for the ceremony. The worship room was approximately 60 feet wide, 80-100 feet long, and more than a story high. There were windows on both the left and right sides of the space and skylights. The

focal point was the front of the room, where there was an altar that was closed off by a curtain. Before the ritual started, the curtain was opened. The shrine itself is on the wall of the back of the altar. The shrine doors on the altar were closed, but the priest later opened them during the service. Despite the wall hangings, the space felt simple, with its glowing,

blond wood paneled walls. There was a huge drum in the left rear of the room and another on the altar. There was a portable shrine in the back right of the hall, as well. There was a giant wood carving of a face above the windows on the left wall. Most of the cloth hangings had a triple flame ('mitsu' tomoe) symbol on them.

focal point was the front of the room, where there was an altar that was closed off by a curtain. Before the ritual started, the curtain was opened. The shrine itself is on the wall of the back of the altar. The shrine doors on the altar were closed, but the priest later opened them during the service. Despite the wall hangings, the space felt simple, with its glowing,

blond wood paneled walls. There was a huge drum in the left rear of the room and another on the altar. There was a portable shrine in the back right of the hall, as well. There was a giant wood carving of a face above the windows on the left wall. Most of the cloth hangings had a triple flame ('mitsu' tomoe) symbol on them.  arms, but elementary school aged children were also present. I saw no teenagers. By and large, the observers were wearing modest street clothing. The website requested no jeans, no shorts, and no bare feet, but I saw a few pairs of dungarees and some bare feet. The ushers wore western clothes, primarily suits or jacket and tie, with a short, green robe covering their upper body. They were all sock-footed. The priest and some of the attendants were dressed in what I took for the same gi that I wore when I took aikido and karate: a white, belted, wrap top and white pants. The priest wore another white robe with elaborate sleeves over his gi, and he wore a black hat. Two of the attendants wore dark blue or grey hakama over the gi trousers. The third simply wore the gi. The woman who later danced, as an offering to the kami, also wore a white gi, but with a pink and gold gossamer cape/robe over it; she also wore an elaborate headpiece. The priest and the other people wearing gi all wore white tabi socks.

arms, but elementary school aged children were also present. I saw no teenagers. By and large, the observers were wearing modest street clothing. The website requested no jeans, no shorts, and no bare feet, but I saw a few pairs of dungarees and some bare feet. The ushers wore western clothes, primarily suits or jacket and tie, with a short, green robe covering their upper body. They were all sock-footed. The priest and some of the attendants were dressed in what I took for the same gi that I wore when I took aikido and karate: a white, belted, wrap top and white pants. The priest wore another white robe with elaborate sleeves over his gi, and he wore a black hat. Two of the attendants wore dark blue or grey hakama over the gi trousers. The third simply wore the gi. The woman who later danced, as an offering to the kami, also wore a white gi, but with a pink and gold gossamer cape/robe over it; she also wore an elaborate headpiece. The priest and the other people wearing gi all wore white tabi socks.  and samisen music. Food, drink, dancing, and evergreen boughs were all presented to the kami. Toward the end, the priest struck the drum on stage repeatedly, presumably to devoke the kami. After the inner doors to the shrine were closed, the priest then turned to the congregation and addressed us in English. He explained that, initially, in Japan, the kami were all thought to live atop mountains, and, only later, did the Shinto come to build shrines to house the kami. The priest further explained that spiritual life of these farmers was thoroughly intertwined with their everyday living. The sun kami would impart his divine energy into the crops by shining on them, and the earth kami would mix the solar energy with its own energy to provide nourishment to the eater when the food was chewed properly. After the ritual ended, we were invited to partake of the now purified sake from the ceremony.

and samisen music. Food, drink, dancing, and evergreen boughs were all presented to the kami. Toward the end, the priest struck the drum on stage repeatedly, presumably to devoke the kami. After the inner doors to the shrine were closed, the priest then turned to the congregation and addressed us in English. He explained that, initially, in Japan, the kami were all thought to live atop mountains, and, only later, did the Shinto come to build shrines to house the kami. The priest further explained that spiritual life of these farmers was thoroughly intertwined with their everyday living. The sun kami would impart his divine energy into the crops by shining on them, and the earth kami would mix the solar energy with its own energy to provide nourishment to the eater when the food was chewed properly. After the ritual ended, we were invited to partake of the now purified sake from the ceremony.